On a number of occasions I’ve been asked to suggest a productivity metric for technical writers, usually as part of a performance management initiative.

When it comes to metrics, I’m more in the “Not everything that counts can be counted” camp than in the “If it can’t be measured, it can’t be managed” one. But if you are required to devise a metric, you owe it to your team and company to come up with something that is workable and fair.

At its simplest, productivity is the rate at which work is done:

Work ÷ Time = Productivity

But this isn’t very helpful. Obviously, churning out reams of pointless documentation like Tina the tech writer isn’t useful productivity.

In his blog post Technical Communication Metrics: What Should You Track? Tom Johnson quotes Jack Barr and Stephanie Rosenbaum, who define productivity as:[1]

(Quality × Quantity) ÷ Time = Productivity

This is an improvement, but it’s still missing something. We need to take into account that not all (tech doc) work is equally difficult: writing up a procedure for a consumer application is easier than explaining the workings of a complex fraud detection algorithm.

So at the very least we need to add complexity to the formula:

(Quality × Quantity × Complexity) ÷ Time = Productivity

Now we need to find reliable measures for each of the four variables on the left.

Time

Time is relatively easy, provided your team members are already logging their time. If not, you might be able to get by with estimates.

Complexity

Complexity can be incorporated by agreeing on a set of weightings for different document types (or work products):

| Work product | Complexity weighting |

|---|---|

End user guide |

1.0 |

Administrator guide |

1.5 |

Developer guide |

2.0 |

Quantity

Measuring quantity is where developing a workable productivity metric starts to get tricky. You need to measure something that represents the bulk of the work being done, and it should be independent of time.

One way to measure raw quantity in technical documentation is to count the number of words that technical writers write in a given period. Word counts have a bad reputation because they can perversely incentivize verbosity and disincentivize other productive, even essential activities. For example, technical writers might be discouraged from considering other, possibly more effective, approaches to conveying information, such as diagrams and images. Even more importantly, prioritizing word counts could discourage planning and design, which according to JoAnn Hackos[2] should account for 30 percent of a documentation project’s time.

How can these perverse effects be countered?

One option is to add additional quantity variables relating to important work products. But this is likely to be impractical: even if you can arrive at a weighting for diagrams versus words, how would you take into account the value of planning, especially planning that obviates unnecessary work?

An alternative is to rely on the quality variable. The idea is that if you have a valid measure of quality, you can ensure that those aspects of the technical writers’ job that are not directly measured are nevertheless accounted for through their impact on quality. Not including diagrams where they would be helpful will drag down the quality rating. Conversely, adequate time spent on planning and design should be reflected in an increased quality score. This, however, makes measuring quality accurately even more critical.

Determining word counts is easy when writing new documents but can prove more difficult when updating documents. If a writer adds 400 new words but deletes 100 old words, you would presumably want the word count to be 400 words not 250. And similarly, if a writer rewrites a section, you’d want to credit them for that work.

Quality

Being able to put the (Quality × Quantity × Complexity) ÷ Time = Productivity formula into operation, heavily depends on devising a reliable measure of quality. Below, I propose two ways of doing this:

-

Using a quality rating

-

Using the reviewer time–writer time ratio

Quality rating

One way of measuring quality is to ask expert reviewers and editors to provide a quality rating for each new document or update. This can then be incorporated into the productivity calculation:

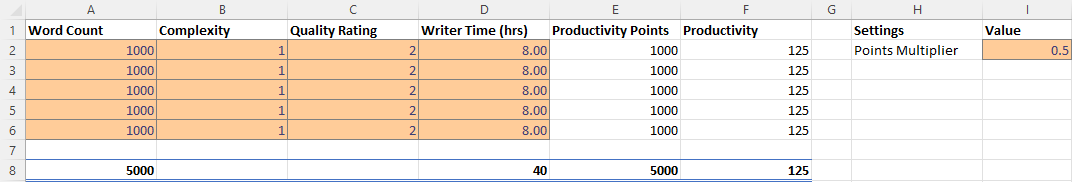

The formula used to calculate productivity points (column E) is:

=@WordCount*@Complexity*@QualityRating*PointsMultiplier-

WordCountis the number of words added or rewritten. -

Complexityis a scale like the one proposed above. -

QualityRatingis a value on a five-point scale from 0 (Unacceptable) to 4 (Excellent). This is essentially the same as the scale employed by Carey et al.,[3] except zero-based. -

PointsMultiplieris simply used to adjust the output of the formula to convenient values.

Productivity points do not have time as a denominator, unlike productivity (column F).

This means that you don’t actually need to track time for individual tasks.

Instead, you could simply set team members a target for a defined period, such as a 40-hour week.

For example, using a PointsMultiplier value of 0.5, you might set team members a minimum target of 5000 productivity points per week, equivalent to 1000 words per eight-hour day, of average complexity (1) and average quality (2).

Individual team members might meet this minimum target in different ways:

-

One writer might work on developer documents assigned a complexity of 2 and so need to write only 500 words a day.

-

Another writer might consistently achieve a quality score of 3 and so require only about 670 words a day.

-

And a third, relatively weak, writer might find that they have to produce 2000 words a day to make the target because their writing is consistently assigned a quality rating of only 1.

The formula could be refined. For example, you might distinguish content-level quality (accuracy, completeness, and relevance) from form-level quality (structure, language, and style). The former would be assessed by the subject-matter expert and the latter by an editor. You could even make use of a document review checklist, such as the one provided by Carey et al.[4]

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

Reviewer time–writer time ratio

An alternative to using an explicit quality rating is to find a reasonable proxy for it. I believe that this can be done using the ratio between the time spent reviewing and editing a document (reviewer time) and the time spent creating or updating it (writer time). The idea is that writers who are producing good quality work will consistently require relatively less time from reviewers and editors. Weaker writers require more time from subject-matter experts to check and correct content and from editors who need to perform structural editing.

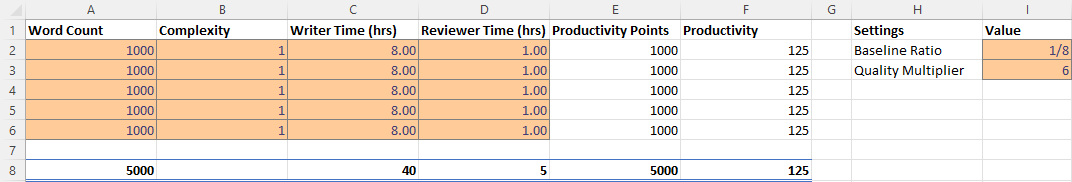

The formula for calculating productivity points is now:

=(@WordCount*@Complexity+(@WordCount*-((@ReviewerTime/@WriterTime)-BaselineRatio)*QualityMultiplier))-

WriterTimeis the total amount of time logged by the technical writer in creating or updating the document. -

ReviewerTimeis the total amount of time logged by reviewers and editors of the document. -

BaselineRatiois the ratio of reviewer time to writer time that neither increases nor decreases the product ofWordCount×Complexity. -

QualityMultiplieris used to weight the effect of the reviewer–writer ratio on the overall productivity score.

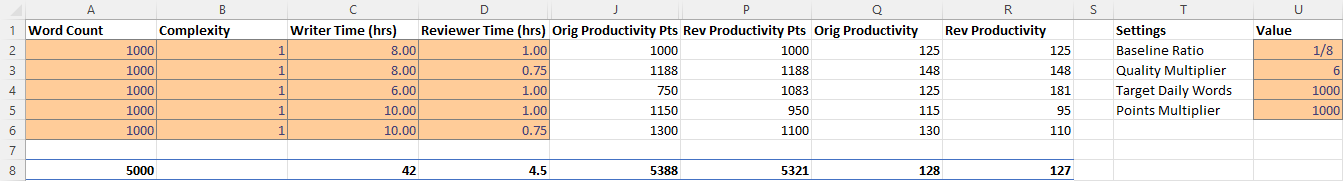

As with previous approach, it is possible to arrive at a minimum weekly target of 5000 productivity points. As shown above, with the baseline ratio specified as 1/8 and the quality multiplier set to 6, this is equivalent to 1000 words of average complexity (1) per eight-hour day, requiring 1 hour of review time.

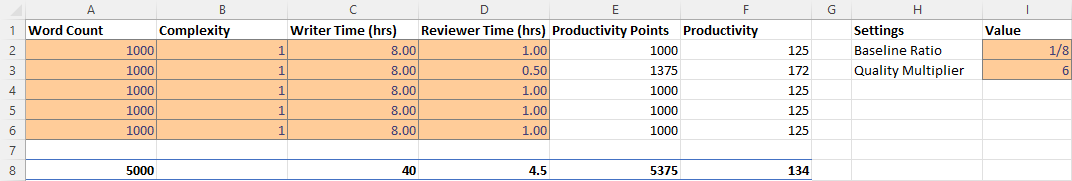

If a technical writer spends 8 hours writing 1000 words, but the reviewers require only 0.5 hours, then the writer will earn 1375 productivity points (row 3):

The reasoning is that the technical writer has produced a higher quality product requiring less remedial input.

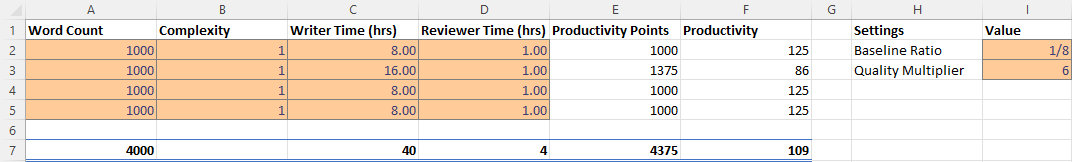

But what happens if the technical writer takes longer on the task without a reduction in the reviewer time? Consider a case where a technical writer takes twice as long to complete 1000 words (row 3):

The writer would again earn 1375 productivity points instead of 1000. However, notice that they are earning points at a slower rate, so that within the 40-hour week they will earn a total of only 4375 productivity points (all other tasks being equal). Nevertheless, it still seems a little counter-intuitive for the writer to receive more productivity points for the same output.

In order to arrive at an output that better fitted my expectations, I included the ratio between the word count and the time taken by the writer in the formula:

Or as an Excel formula:

=(((@WordCount/@WriterTime)/(BaselineRatio*TargetDailyWords))-(((@ReviewerTime/@WriterTime)-BaselineRatio)*QualityMultiplier))*PointsMultiplier-

TargetDailyWordspecifies the number of words that technical writers are expected to produce per day. -

PointsMultiplieris used to adjust the output of the formula to convenient values. If thePointsMultiplierequalsTargetDailyWords,Complexityis 1 and the review–write ratio is equal to the specifiedBaselineRatio, each word will result in one point.

Fundamentally, the formula boils down to WordCount/WriterTime - ReviewerTime/WriterTime.

The effect is that changes to the reviewer time influence the score as before, but changes to the writer time are “counteracted” by the word count–writer time ratio.

The image below shows how this works:

Notice that in row 3, as the review time decreases, the productivity points resulting from the original formula (column J) and the revised formula (column P) both increase. However, when in row 4 the writer time is reduced, the resulting productivity points are different. Using the revised formula, the productivity points increase. I believe this is more intuitive: the writer is producing the same amount of work in less time while requiring no greater effort by the reviewers (implying constant quality), so is more productive.

Similarly, in row 5 when the writer takes longer to do the work while requiring the same amount of effort from the reviewers, the revised formula results in fewer productivity points, which intuitively seems correct. But if the writer’s increased time results in even a modest reduction in the effort required by the reviewers (row 6), the writer is rewarded with more productivity points. This should incentivize writers to balance quality and quantity.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

In short

I’ve suggested two ways of tracking technical writers’ productivity both of which rely on a measure of the intrinsic quality of documents:

-

A quality rating reflects a reviewer’s assessment of intrinsic qualities of the document, such as completeness, accuracy, clarity, organization, style, and so forth.

-

The claim I’ve made is that the reviewer time-writer time ratio is a proxy for this sort of measure of intrinsic quality.

In a later post, I’ll consider other ways of measuring quality (and by extension, productivity), including extrinsic measures like user ratings.

I’d love to hear what you think. Do either of the approaches outlined above seem workable, or are they just metrological madness?

If you’d like the spreadsheets, send me a request via LinkedIn or using the comments below.